The archaeology of Allied convoy attacks by U-322

By Tanja Watson, Historic England

U-322, a German Type VIIC/41 U-boat, departed Horten Naval Base, south of Oslo, Norway, for her second combat patrol on 15 November 1944. Embarking on a less trafficked route around northern Scotland and western Ireland, she entered, nearly six weeks later, the heavily patrolled and mined waters of the western English Channel.

This is an account of the archaeological evidence left when she came across two Allied convoys within the space of six days.

The Type VIIC/41 submarine, one of ninety-one made, was built in 1943 by the Flender Werke yard at Lübeck, and was commissioned on 5 February 1944 under the command of twenty-four-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Gerhard Wysk. After completed training, she began her operational career with the 11th Flotilla on 1 November, departing from Kiel to Horten Naval Base the following day with the standard 52 men onboard. [1]

The 11th U-boat Flotilla was stationed in Bergen (Norway) and mainly operated in the North Sea and against the Russian convoys in the Arctic Sea. The U-322, however, was ordered to Britain and departed nine days after arriving at Horten.

At this late stage in the war, new Allied convoy tactics and technology, using high-frequency direction finding and the Hedgehog anti-submarine system, made any patrol a high risk, but particularly in the confined waters of the heavily protected English Channel a strong possibility.

The first convoy she encountered, MKS 71G (Mediterranean to the UK Slow), was an Allied convoy going from North Africa via Gibraltar to Liverpool. It was made up of 24 merchant vessels (the majority British) and seven escorts which had departed from Gibraltar on 16 December, was due to arrive in Liverpool on 24 December. [2] At 11.50 hours on 23 December 1944, the British-built but Polish-owned steam merchant SS Dumfries carrying 8,258 tons of iron ore from Bona, Algeria to the Tyne, was torpedoed and sunk by U-322 south of St. Catherine’s Point, Isle of Wight. [3]

The crew onboard the vessel, which was owned by Gdynia America Shipping Lines Ltd, Gdansk [4] were rescued by HMS Balsam, a Flower-class corvette who picked up the master (Robert Blackey) and seven crew members, landing them at Portsmouth; and HMS Pearl, an anti-submarine trawler, who picked up the remaining 41 crew members, eight gunners and two passengers, taking them to Southampton. [5]

The sinking of Dumfries was for many years attributed to U-722, but its involvement was disproved after its wreck was discovered elsewhere. [6]

The Dumfries wreck was most recently recorded by the UK Hydrographic Office [UKHO] in 2007 and noted it was sitting upright on a bed of gravel at a depth of 37 metres, largely intact. The remains are 11-12m high, 120m long, and 18m wide with a starboard lean and showing signs of breaking up. [7]

The second convoy encounter occurred seven miles southeast of Portland Bill Lighthouse on the 29 December 1944. This convoy was TBC-21, the Thames Estuary to the Bristol Channel route, bound from Southend in Essex to Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire, Wales. [8]

No longer equipped with her full torpedo load (14), after the attack on Dumfries, U-322 launched at least two torpedoes at the convoy which struck two large US Liberty ships within minutes of each other.

The first to be hit was the SS Arthur Sewell, the fourth ship in the port column. Travelling from Southampton for Mumbles, Wales, she had joined the convoy part of the way for protection. The 7,176-ton American cargo vessel was severely damaged, but the ship held and a tug, HMS Pilot (W 03), towed her to Weymouth. Five men were injured, and one killed out of a crew of sixty-nine. An injured sailor died the next day.

Built in March 1944 by the New England Shipbuilding Corporation, Portland, Maine, she was under the command of the US Maritime Commission at the time.

After the war she was first towed to Portland, temporarily repaired, and then to Bremerhaven where she was loaded with chemical ammunition, towed to sea and scuttled in the North Sea on 26 Oct 1946. [9] Her remains have yet to be located.

The second Liberty ship to be struck was the SS Black Hawk, the last vessel in the starboard column, travelling in ballast from Cherbourg via the Isle of Wight to Fowey on behalf of the US Army Transport Service. [10]

Four of the ship´s 41 crew were injured, one later died. There were no casualties among the 27-man armed guard. [11] The men were picked up by HMS Dahlia and landed at Brixham at 20.30 hours. [12] There is a photograph of the ship sinking.

The torpedo struck the ship on the port side, and the engines were immediately secured as the ship started to sink by the stern. A crack appeared at the #3 hatch and only the two forward compartments kept the ship afloat.

The vessel broke into two large sections, with the aft or stern end sinking into the sea off the Bill of Portland, while the bow or fore section stayed afloat. [13] This section was towed to Worbarrow Bay where it was beached on 30 December 1944. The site was marked by a can buoy until the Worbarrow Bay pipeline was laid and the large section had to be dispersed, using explosives, in 1968. Today the bow lies at a depth of 13-15m, surrounded by 50m of debris. It can be identified by the heavy anchor chain that runs almost 75m south to a 3-ton anchor. [14]

The large stern end (30 feet) which had sunk off Portland Bill, was discovered in 1963, lying in two sections, on its starboard side with a gun still bolted to its platform, at a depth of 31-45m. Dispersal operations were carried out in November that year. At some point a bronze propeller was salvaged, possibly in the 1970s, according to an image published in Diver Magazine, October 1999. The remains were not identified as potentially a Liberty ship until 1975, with the Black Hawk attribution only confirmed in 1987.

DP 438558 © Historic England Archive

The final wreck that day is that of U-322. Having fatally damaged the two cargo vessels, she was not long after sunk by one of the convoy escorts, HMCS Calgary, a Canadian Flower-class corvette, using depth charges. She went down on 29 December 1944 in the English Channel south of Weymouth. Fifty-two men died; there were no survivors.

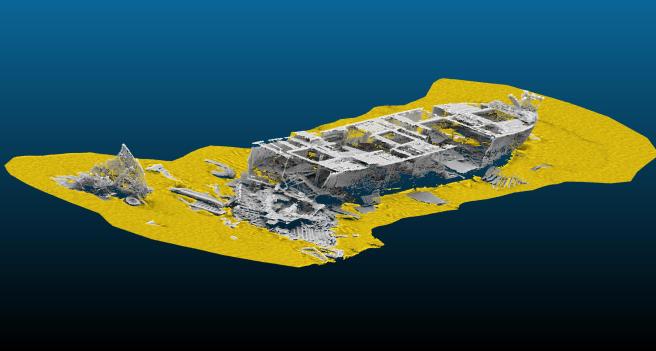

The wreck was identified as U-322 by Axel Niestlé after it had been initially thought that it was U-772. [15] She is recorded by UKHO as intact with extended mast, 59m long x 18m wide at a depth of approximately 42m. [16]

The wreck of the U-322 is part of a distribution of archaeological remains telling the story of one series of attacks by a submarine in WW2.

It illustrates the complications of recording and interpreting the submerged remains with a story of partial sinking, conflicting records, misidentification, salvage, clearance for navigational safety and erasure by development.

Footnotes

[1] uboat.net https://uboat.net/boats/u322.htm

[2] MKS Convoy Series, Arnold Hague Convoy Database, http://convoyweb.org.uk/mks/index.html

[3] Uboat.net, SS Dumfries, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/3396.html

[4] Historic England, NMHR Ref No. 1246514 – record accessed via the Heritage Gateway

[5] Wrecksite, SS Dumfries, https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?4651

[6] See note [3]

[7] UKHO Wreck Record 18917 (Dumfries)

[8] Convoy route TBC, https://uboat.net/ops/convoys/routes.php?route=TBC; TBC-21 http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/hague/index.html

[9] Arthur Sewall, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/3405.html

[10] https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/3405.html and https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/3406.html; https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?78432

[11] Skindeepdiving, Black Hawk

[12] https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/3406.html

[13] UKHO Wreck Report No. 18557 [stern]; UKHO Wreck Report No. 18677 [bow]

[14] See note [11]

[15] https://uboat.net/boats/u322.htm

[16] UKHO Wreck Report 18541