Inspired by my recent holiday in Croatia, I thought I’d turn this week to looking at wrecks in English waters from that part of the world. I’ve touched before on how changing national boundaries and ideas of nationhood affect the way we classify wrecks – the nationality recorded at the time of loss is often very different from the nationality now, and this is as true for Croatia as for the subjects of my previous articles on Estonia, Finland and Hungary.

Croatia has a long and proud seafaring tradition with many rocky islands rising steeply out of the sea, affording little shelter to anyone unfortunate enough to be shipwrecked there. Indeed, Richard the Lionheart caused an ex voto church to be built at Lokrum in 1192. The islands are well marked with picturesque lighthouses and it is worth exploring this fantastic gallery here. Though there may be a number of earlier vessels in our records whose Croatian origins are masked by the lack of detail in contemporary sources, they first come to our attention in English waters during the 19th century, when Croatia was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

One such vessel was Barone Vranyczany, lost in 1881 off Suffolk, named after a local noble family who had Magyarised their surname from the Croatian Vranjican. Her home port had the Italian name of Fiume (now Rijeka): the name of her master, Pietro Cumicich, reflects a dual Italian-Croat linguistic heritage. With the help of the Austrian consul at Lowestoft, acting as interpreter, a fellow master from Fiume identified Cumicich’s body through his wedding ring inscribed with his wife’s initials and the date 10-12-77.

Croatia’s Italian heritage is very strong, reflecting its Venetian past and its proximity to the Italian coast. (The island of Korcula is traditionally said to have been the birthplace of Marco Polo, although this is disputed.) The Croatian littoral passed out of Venetian control to become the Republic of Ragusa, centred on Ragusa itself, now Dubrovnik: the two names, Latin and Croat, existed side by side until 1918 when Dubrovnik alone was officially adopted.

This link is clearly seen in the ship Deveti Dubrovački of Ragusa. She was one of a fleet belonging to the Dubrovnik Maritime Company, whose ships had a very simple house naming scheme. She was ‘The Ninth of Dubrovnik’: all the fleet were likewise named in order from ‘The First of Dubrovnik’ onwards. (1) She met her end in 1887 through a collision with a British steamer off Beachy Head, another wreck that illustrated the bond between husband and wife. The captain tied a rope around his wife, from which she was hauled in her nightdress aboard the steamer, despite her ‘imploring him not to mind her’: alas, she had the misfortune to see her husband go down with his ship. (The fact that the steamer did not also sink in this collision was attributed to the cushioning effect of the wool tightly packed in her hold.) (2)

Several ships have Italian names, such as the Fratelli Fabris, whose remains (1892) are said to lie close to Tater-Du on the coast of Cornwall, and which is known locally as the ‘Gin Bottle Wreck’. Indeed, a 1927 wreck was recorded in contemporary sources as of Italian nationality: the Isabo was built as Iris in Lussinpiccolo (now Mali Losinj, Croatia), then Austro-Hungary, a part of Croatia which became Italian in 1918.

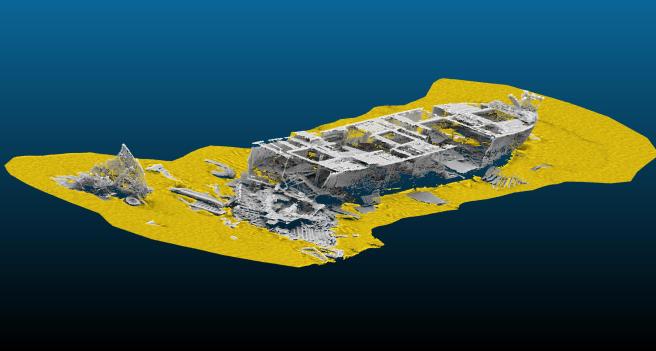

At the same time the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was created, to which the Slava, a war loss of 1940 off Porlock Bay, belonged. Only nine ships out of the country’s fleet survived the war. (3) After the Second World War Yugoslavia became a Socialist Federal Republic, of which Croatia was a constituent part. Our final wreck today is the Sabac, which belonged to that country’s nationalised fleet, and which was lost in 1961 in a collision off the South Goodwin light vessel.

Since 1991 Croatia has been an independent state, but one whose long maritime history endures, intertwined with that of many other nations, past and present. Its heritage is part of our own heritage too, from Lokrum to the wrecks around our coastline today.

(1) Anica Kisić, “Dubrovačko Pomorsko Društvo”, Atlant Bulletin, No.13, July 2004, pp22-4. URL: https://www.yumpu.com/hr/document/view/36424950/srpanj-2004-atlantska-plovidba-dd/23

(2) Edinburgh Evening News, 30 December 1887, No.4,530, p2

(3) http://www.atlant.hr/eng/atlantska_plovidba_povijest.php