The wreck in two places at once

In this blog we’ve occasionally encountered wrecks that are in two places at once. The Mary Rose is a good example: after being raised in 1982, her principal structure lies in the Mary Rose Museum at Portsmouth, but she is still a designated wreck site offshore with some remains still in situ. We’ve also looked at the ship that was wrecked in two separate countries, leaving different bits behind each time.

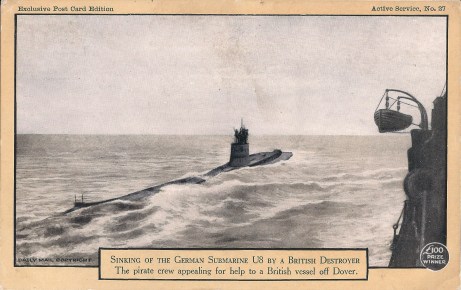

HMS Nubian is another example of a similar phenomenon. One of the Tribal-class destroyers which patrolled the Dover Straits during the First World War (see the story of Viking, Ghurka, and Maori in action against U-8), she was sent out to intercept a surprise Channel raid by the enemy in the early hours of 27 October 1916. A visit by the Kaiser to Zeebrugge had led the Admiralty to expect a German landing west of Nieuwpoort (possibly a diversionary tactic which succeeded in drawing out some of the British naval forces towards Dunkirk?) (1)

There were six Tribal-class destroyers stationed at Dover, with HMS Zulu patrolling out at sea further west, and the net barrage guarded by 28 auxiliary trawlers and drifters, in company with the destroyer HMS Flirt. Against them 24 German destroyers were steaming up Channel: Flirt issued a challenge, which was returned, and they steamed past in the dark, assumed to be part of the British movements that night.

This was a fatal mistake since the first attack of the night resulted in the sinking of HMT Waveney II off the net barrage. Flirt went to her assistance: in the meantime those on board the auxiliary yacht Ombra had grasped the situation, reporting enemy activity to the authorities and ordering the remaining HMTs back to Dover. Flirt herself came under attack at ‘point blank range’ which blew up her boilers, causing her to sink within five minutes. The Queen troopship was then captured and despatched. remaining adrift for about six hours before foundering off the Goodwin Sands. Fortunately she was carrying mail on her run from Boulogne to Folkestone, rather than troops.

By this time the destroyers in Dover were steaming out to investigate. As Nubian approached the net barrage destined to snare submarines, she was on her own without support, though by now further assistance was coming from the Dunkirk and Harwich quarters, attempting to trap the German force in a pincer movement.

Six of the retreating patrol drifters, four of which were unarmed, were then sunk by the German raiders – Spotless Prince, Launch Out, Gleaner of the Sea, Datum, Ajax II and Roburn (which had also been involved in the engagement with U-8)

The Nubian reached 9A Buoy in the net barrage, from which the commotion had come, then turned about – straight into the German 17th Flotilla steaming towards her. The first two enemy torpedoes missed, but the third found its target and blew off her bows. The rest of the ship was taken in tow, but, as a gale sprang up, she drove ashore near the South Foreland.

You might think from the title of this article that that’s it: Nubian now rests in two places: in mid-Channel and near the South Foreland. In fact, her story is much more interesting than that. We return now to a bit-player in the events of 26-27 October 1916, HMS Zulu: a minefield in the Straits of Dover would ‘terminate her career’, in the words of the official history. (2) On the afternoon of 8 November 1916 she struck a mine which ‘shattered her after part’, with her bow section being towed to Calais.

Something of a pattern was emerging here . . .

In what was later described as a ‘grafting’ operation, (3) using the language of the pioneering plastic surgery techniques which emerged out of the injuries of the First World War, the two grounded sections – the bow section of Zulu and the aft section of Nubian – were salvaged, joined together and given the portmanteau name HMS Zubian.

As Zubian, therefore, both wrecks rejoined the Dover Patrol. Who knows how many times she passed over the remains of her component ships below?.She would later be credited with ramming UC-50 (a misidentification: probably UC-79) (4) and would participate in the Zeebrugge raid of 23 April 1918. Several of the Tribal-class were disposed of in 1919 : unsurprisingly, Zubian was among them, after everything she had been through. (5)

Nubian was the ship that was salved because another ship was wrecked: fortuitous and resourceful recycling in a time of war.

(1) Naval Staff Monographs, Vol. XVII. Home Waters, Part VII: June 1916 to November 1916 London: Admiralty, 1927, p185-189. The acccount here is principally derived from this source, supplemented by information from the wreck records in the National Record of the Historic Environment for each vessel lost (see links).

(2) ibid., p208

(3) The Times, 28 February 1935, No.47,000, p13

(4) uboat.net

(5) The Times, 22 November 1919, No.42,264, p9