1918/1928

Q-ship Stock Force was the only ship to sink off the coast of Devon on 30th July 1918, despite her best efforts to sink the attacking U-boat. In fact it seems she may have been the only Allied vessel to have sunk anywhere in the world that day (although there were some unsuccessful U-boat attacks on the same day that damaged, but did not sink, the victims). (1)

Yet it could be said that Stock Force was not the only ship which sank as a result of that day’s engagement. There was a (very) delayed knock-on effect which came about through the post-war publicity generated by news of the event and the celebrity attached to her successor Suffolk Coast, which went on tour with the same crew. There were many popular naval memoirs, too, including Auten’s own. (2)

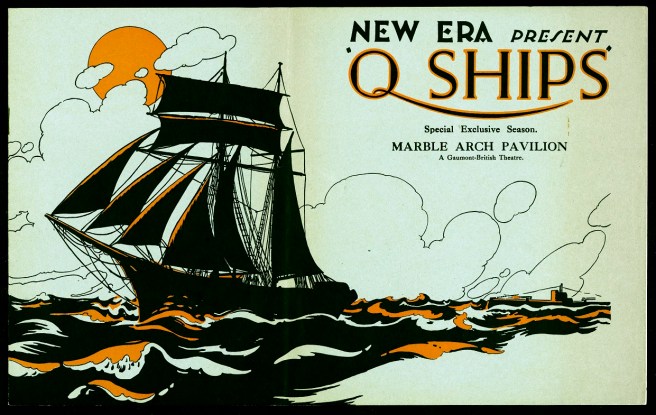

This suggested that even in the crowded market of wartime films a movie on the theme of Q-ships would be popular, and it was announced in late 1927. (3)

Its authenticity was a major selling point: ‘Reality and not “fake” will be the keynote of this production’. (4) Genuine and re-enactment footage were spliced together: as a review stated, ‘It is difficult to know at times when the “official topical” finishes and when the reconstruction of today starts, so fine is the production work and the editing.’ (5)

Harold Auten was a key stakeholder in the production: the film was largely based on his Q-boat Adventures and Stock Force‘s final battle, he was the film’s naval consultant, and he and five of his crew also reprised their wartime roles ten years on for the purposes of the film, together with ‘the actual gun’ from Stock Force.

After all, they had form as actors in keeping up the role of merchant seamen for months on end while on the lookout for U-boats! A U-boat captain, Hermann Rohne, was taken on board as U-boat consultant, while Earl Jellicoe played himself as Admiral Jellicoe of Jutland fame.

The cast was the easy part. Re-enacting naval engagements was much harder, with a number of practical hurdles to overcome. First of all, the 1917-built Southwick replaced Stock Force, now at the bottom of the sea.

There were no longer any genuine U-boats, which had all been surrendered in 1918-19 and broken up in the early 1920s as directed by the Treaty of Versailles. However, two obsolete submarines were placed on the disposal list in 1927 and H-52 was accordingly purchased by producer E Gordon Craig as a stand-in for a U-boat.

She was intended to be sunk in a set-piece battle off the Eddystone in January 1928. but she was very nearly wrecked en route to being sunk (and in this resembles the real U-boats so often taken in tow post-war for breaking, when the sea accomplished the task intended for the breaker’s yard: see our previous post on this subject).

Under tow out to sea, she missed the harbourmaster’s launch by inches, crashed into a jetty without somehow managing to set off the demolition explosives with which she was packed, then broke tow. Arriving on location, they were forced to turn back and nearly lost the craft again when she went aground. (6)

On the final successful attempt, the submarine lay off the Eddystone, while guns from the Southwick, representing the Stock Force, fired 8 rounds into H-52, sinking the submarine and reversing the fortunes of the original event. ‘There was a sudden explosion and a high column of smoke and debris as the submarine blew up just fore of the conning tower. One hundred pounds of TNT had been stacked in her for this realistic touch, and this was set off by an electric lead to the naval boat.’ (7)

The wreck has been charted ever since January 1928, and has a detached bow and associated debris field consistent with her manner of loss. (8)

She joined a long heritage of naval vessels being repurposed at the end of their service lives – from 17th century accounts of wooden sailing vessels being used as foundations for new harbours, to 20th century warships and submarines being expended as gunnery targets, to the sinking of HMS Scylla as an artificial reef in 2004, but being expended for a film re-enactment is perhaps a little more unusual!

Another elderly vessel of mercantile origin, the schooner Amy, was also purchased to stand in for the schooner Prize in the film (the German schooner Else captured as a prize of war on 4 August 1914, hence her change of name). Prize was converted into a Q-ship and underwent three actions, being lost with all hands on her last battle with a U-boat. (The National Maritime Museum holds a watercolour of one of her previous actions.)

Amy was described as having been ‘one of the oldest sailing ships afloat’, built at Banff and 65 years of age on her first and last appearance on screen. This seems to refer to the Banff-built schooner Amy, official no.62443, which was, in fact, built in 1870 (and so was ‘only’ 58) and whose register was closed in 1928. (9)

Far from being a potential candidate for preservation, this ‘Grand Old Lady of the Sea’ (10) was selected to represent Prize in her final battle, which can also be viewed as an elegy for the sailing vessel in the light of the havoc wrought by the First World War.

She too was sunk ‘in action’ off the Bill of Portland in February 1928, and again it took several attempts, blamed on the removal of her figurehead as a souvenir. Much was made of this in the press, with superstitious sailors saying that to be successfully sunk she should have her figurehead with its ‘lucky squint’ reinstated! If nothing else, it was certainly a good story to drum up interest in the film. (11)

Amy has also been consistently charted at her position of loss since 1928 and has a unique place in the maritime heritage of England’s Channel coast. In being expended for re-enactment purposes, she can lay claim perhaps to being the final (indirect) victim of the First World War at sea in English waters (there were other direct post-war losses but we will cover that in a future edition of Wreck of the Week). She is also a rare, if not unique, example of the wreck of a Victorian sailing vessel documented in the early days of 20th century film. And finally, she has the sad distinction of being a counterpart to a genuine wartime loss, whose remains are yet to be discovered.

The Q-Ships film created – and documented in the very creation – a heritage of its own.

(1) Lloyd’s War Losses: The First World War: Casualties to Shipping through Enemy Causes 1914-1918, facsimile edition, 1990, London: Lloyd’s of London Press Ltd; uboat.net

(2) Q-boat Adventures, 1919, London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd.

(3) Western Morning News, Friday 25 November 1927, No.21,115, p5; Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 2 December 1927, No.3,114, p14

(4) Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 2 December 1927, No.3,114, p14

(5) The Stage, Thursday 28 June 1928, No.2,465, p24

(6) Western Morning News, Monday 2 January 1928, No.21,146, p5

(7) Belfast News Letter, Wednesday 4 January 1928, no issue number, p7

(8) UKHO 17584

(9) Entry for Amy on www.clydeships.co.uk

(10) New Era Presents: Q-Ships souvenir programme, 1928

(11) Dundee Courier, Monday 26 March 1928, No.23,340 p5